The book “The Great Influenza” by John Barry vividly describes how the Spanish flu became much deadlier within a few months because it was able to adapt better to humans. If a pathogen kills too quickly right from the start, too many people die in a short time and the pathogen no longer finds enough more people to infect.

A pathogen jumps from animals to humans and is moderately dangerous at first. More and more people become infected and spread the pathogen, which is then able to adapt better and better to humans. At some point it is then very dangerous for humans. The second wave of the Spanish flu was a devastating blow that hit the world unprepared.

In Camp Devens near Boston, 1543 soldiers became ill in a single day. Soon, 20% of the entire camp was infected. 75% of the sick needed medical attention. The devastating pneumonias and lightning-fast deaths followed. Doctors and nurses also died. Dr. Roy Grist explained: It starts out normally, then comes the most brutal form of pneumonia you can imagine.

In 1993 Claude Hannoun, the leading expert on the 1918 flu at the Institut Pasteur, claimed that the precursor virus probably came from China. It then mutated in the United States, near Boston, and from there it spread to Brest, France, to the battlefields of Europe, the rest of Europe and the rest of the world, with Allied soldiers and sailors being the main spreaders.

In 2014, historian Mark Humphries argued that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese workers working behind British and French lines may have been the source of the pandemic.

October 1918 was the month with the highest mortality rate in the entire pandemic. The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections had become immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu.

Antigen drift and antigen shift

Viral genome mutates and in most cases this does not result in an advantage for the virus but in a disadvantage. In a tiny fraction of cases, however, the mutations can bring benefits and it is clear that mass distribution increases the likelihood that a virus will adapt better to humans.

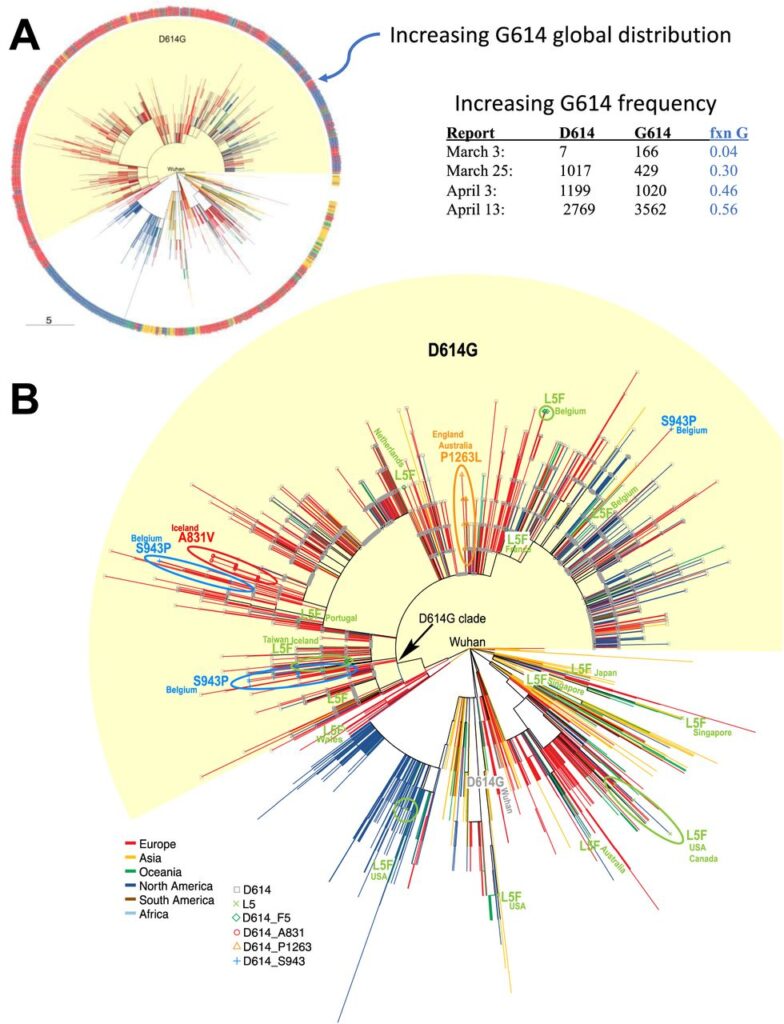

Scientists have identified a new strain of the coronavirus that has become globally accepted and appears to be more infectious than the versions that spread in the early days of the COVID 19 pandemic. This is the result of a new study led by scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory. In addition to faster spread, the mutation could leave people vulnerable to a second infection after a first illness, the report warned.

The 33-page report was published Thursday on BioRxiv, a website that researchers use to present their work prior to peer review to accelerate collaboration with scientists working on vaccines or treatments against COVID-19.

The mutation identified in the new report affects the now infamous spikes on the outside of the coronavirus that allow it to enter human cells.

The Los Alamos team, supported by scientists from Duke University and the University of Sheffield in England, identified 14 mutations.

Three interrelated factors make this disease so dangerous: people have no direct immunological experience with this virus, so we are vulnerable to infection and disease; it is highly transmissible; and it has a high mortality rate. Its rapid global spread gives the virus ample opportunity for natural selection to produce rare but beneficial mutations. If the pandemic does not abate, this could exacerbate the potential for antigen drift and the accumulation of immunologically relevant mutations in the population during the year. The incidence of mutation G614 increased at an alarming rate during March, and there was clear evidence of an ever-increasing geographical spread. The earliest D614G mutation in Europe was identified in Germany. We were concerned that the D614G mutation, if it could increase transmissibility, could also affect the severity of the disease. We did not expect such dramatic results so early in the pandemic. This research shows that viruses with the Spike D614G mutation are rapidly and repeatedly displacing the original Wuhan form of the virus worldwide.